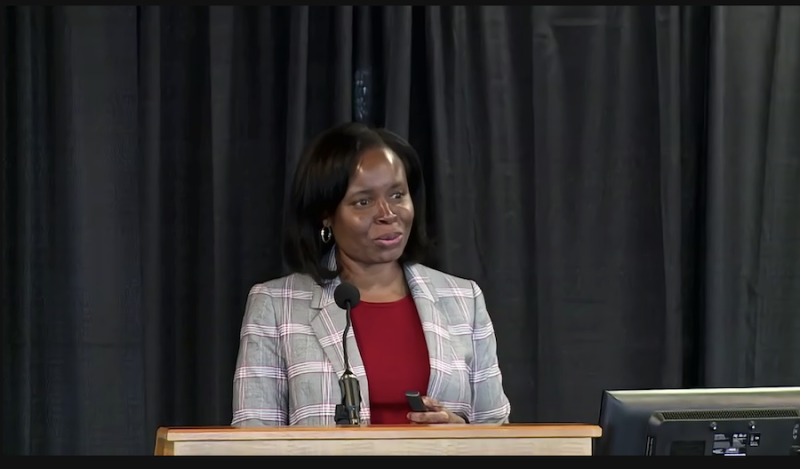

Kimberly Johnson, MD, director of the Duke CTSA KL2 Program, presented her research on equity in serious illness care for African Americans during the final installment of Duke School of Medicine’s Dean’s Distinguished Research Series.

Johnson spoke about two research projects during her lecture, one funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) and one conducted with the AME Zion Health Advocates & Liaisons (HEAL) partnership.

Through her years of research on the topic, Johnson has found that African Americans are less likely to receive high quality serious illness care when compared to white Americans. African Americans are also less likely to access services such as hospice and palliative care and report worse symptom management and communication with providers.

Johnson’s lecture particularly focused on advance care planning. Research shows that African Americans are less likely to discuss advance care preferences for care in the event of a serious illness or at the end of life.

“At the time that we started this work, there were a number of gaps in the existing literature about advance care planning interventions specifically,” Johnson said. “There were often small studies done, not powered to detect differences in racial subgroups, such as African Americans, like in other areas of research.”

Through an opportunity spearheaded by PCORI, Johnson and her team were able to expand their research to examine racial disparities in advance care planning more closely. Through collaborations with local community advisory boards and the Community Consultation Studios (CCS), sponsored by Duke CTSI’s Community Engaged Research Initiative (CERI), Johnson was able to gain community buy-in and input for her research.

Johnson went on to explain that through her research, she discovered that the main barriers impacting advance care planning among African Americans were a lack of knowledge of the process, hesitance in discussing and planning for death, lack of trust in health care providers, and spiritual beliefs. She and her team examined whether racial concordance impacted advance care planning, recruiting nearly 800 participants across five states and 10 clinics and pairing them with an interventionist of the same or different race.

Johnson’s research, which is still ongoing, showed while African Americans in this study were more likely to classify their health as “poor” or “fair,” they were also less likely to share their end-of-life preferences with family members. A common barrier to advance care planning among African Americans in the study was preferring to “leave it in God’s hands”.

“I thought, “is this a barrier related to preferring to leave these decisions in God’s hands?”” Johnson said. “I then thought, “why can’t we bring this kind of education into the community?” Specifically, in churches where people could learn about these things before they actually needed them.”

Johnson and her team worked with AME Zion HEAL to create Equal SPACE (Spiritual and Faith-Based Advance Care Planning and Palliative Care Education), a spiritual and faith-based educational program focused on advance care planning and palliative care. Johnson and her team worked with AME Zion pastors across North Carolina to speak with congregants about what aspects of education would be important as they design their curriculum.

Through both studies, Johnson said she has been able to take advantage of some great community engagement resources at Duke that have been instrumental to her projects’ successes.

“This engagement is an extremely powerful tool for your research, and there's a full spectrum,” Johnson said. “We've had the opportunity to really cultivate bi-directional relationships that have been longitudinal, allowing us to really be open to opportunities to engage with community partners even when they don't initially exist.”